Performance management is a top priority for organisations looking to navigate change. One of the most effective ways to measure performance is through dynamic and rhythmic goal-setting. As employees move back to the office, leaders are again having to transition and learn. What is OKR goal setting and how can it support hybrid workforce performance in times of change?

Performance management in times of change

Performance management is a top priority for organisations looking to navigate change. COVID-19 has disrupted many normal operations for companies, challenging leaders to quickly rethink and rebuild their models of performance for remote work arrangements. As employees move back to the office, leaders are again having to transition and learn — this time from a remote to a hybrid workplace.

One of the most effective ways to measure performance is through dynamic and rhythmic goal-setting. Unlike traditional performance management, where goals are set and revisited once or twice a year, dynamic goal-setting includes clear, agile, team-oriented goals that drive actions and align individuals to the mission and purpose of an organisation.

In today’s hybrid environment, frequent communication and company-wide alignment are imperative. As top-tier priorities change at a faster pace, employees need to both adjust and understand the reasons and value behind the decisions leaders make. A highly effective goal-setting methodology that works for companies of all sizes and is designed to scale is the OKR (objectives and key results) framework.

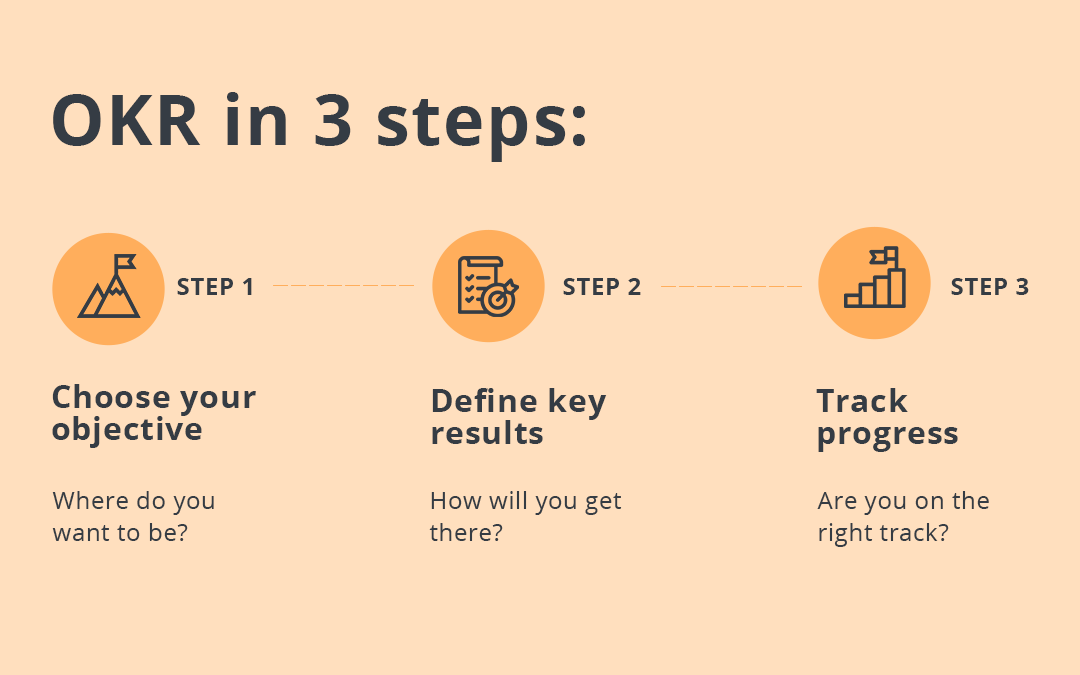

OKRs stand for objectives and key results. The methodology was originally conceived at Intel by former CEO and management guru Andy Grove. It was later pioneered by John Doerr, chairman of venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins, and one of the earliest investors at Google. The framework pairs the objectives you want to achieve with the key results you’ll use to measure progress—so your goals are tied to your team’s day-to-day work.

Born in times of change

When John Doerr joined Kleiner Perkins in 1980, he brought with him a radical new management methodology that would revolutionise Silicon Valley. He had spent the previous five years at Intel, where he worked under management guru Andy Grove. At the time the company was transitioning from a memory company to a microprocessor company. Grove and the management team needed a way to help employees focus on a set of priorities in order to make a successful transition. As Grove explained in his book High Output Management, there are two questions to be answered to successfully set up a system of shared objectives:

Where do I want to go? This answer provides the objective.

How will I pace myself to see if I am getting there? This answer provides the milestones, or key results.

Intel Management by Objectives emerged in this environment and was later simplified to Objectives and Key Results (OKRs). The management framework helped leaders at Intel communicate priorities, maintain alignment, and ultimately effectively navigate the shift they needed to make.

Andy had created this system for goal setting that was deceptively simple, but also the polar opposite of the conventional management by objectives (MBO) systems, which tend to be top-down, hierarchical, annual, and linked to compensation.

How do OKRs work at Google?

OKRs work on the revolutionary idea that teams perform better by focusing on outcomes rather than procedures. Instead of telling employees precisely what to do, Grove would set them goals and let them work out how to achieve them.

Julia Martins explains that OKRs “follow a simple but immensely flexible template that bends and bows to fit nearly every purpose”:

The Objective (O): the goal you want to achieve, for example increasing brand awareness or creating the lowest carbon footprint in your industry.

The Key Result (KR): the metric by which you’ll measure your progress towards your objective, for example drive one million web visitors or ensure one-quarter of your product’s material is compostable.

Google was one of the early adopters of the OKR system, introduced to the leadership team by Doerr in 2000. At Google, OKRs include the following principles:

- Objectives are ambitious and may feel somewhat uncomfortable

- Key results are measurable and should be easy to grade with a number, for example Google uses a scale of 0 – 1.0.

- OKRs are public so that everyone in the organisation can see what others are working on

- The “sweet spot” for an OKR grade is 60% – 70%; if someone consistently fully attains their objectives, their OKRs aren’t ambitious enough and they need to think bigger

- Low grades should be viewed as data to help refine the next OKRs

- OKRs are not synonymous with employee evaluations

- OKRs are not a shared to-do list

Goals are often set just beyond the threshold of what seems possible – referred to as “stretch goals”. These stretch goals are the building blocks for remarkable achievements in the long term, or “moonshots”. One may think that creating unachievable goals could set a team up for failure. However, more often than not, Google has found that such goals can tend to attract the best people and create the most exciting work environments. Moreover, when one aims high, even failed goals tend to result in substantial advancements. The idea is to enable teams to be ambitious, even if they don’t fully attain the stated goal. This helps employees step out of their comfort zones, prioritise work, and learn from both success and failure:

The key is clearly communicating the nature of stretch goals and what are the thresholds for success. Google likes to set OKRs such that success means achieving 70% of the objectives, while fully reaching them is considered extraordinary performance.

Employees at Google set their objectives at the beginning of the month and post the results (along with the objectives) on a forum that is visible to all. Sundar Pichai famously set the objective of creating the best web browser in the world and he was very specific about the Key Result – have twenty million users. He was clear about his purpose and had a very specific goal, that’s what drove him to the creation of Google Chrome in 2008.

Bringing OKRs home: communication is key

Even though most companies set goals, research has shown that only 26% of employees have a clear understanding of how their individual work contributes towards company goals. This is the result of setting goals at the beginning of a year or quarter, then never revisiting them again. However, when employees clearly understand the relationship between their work and their company’s objectives, their motivation doubles.

According to Google, the first step to introducing OKRs to your organisation is to be clear about what they are, why they are helpful and how they will be used. Transparency and buy-in are key components for success. Once the organisation knows what it’s focused on and how it will measure success, it can become easier for employees to connect their projects with the organisational objectives.

If you are interested in learning more about OKRs, watch the Google’s OKR presentation here.